The Military Shrine of Redipuglia, the largest Italian funerary monument (and one of the largest in the world), houses the bodies of over one hundred thousand fallen soldiers from World War I in the northern town that gives it its name, in the province of Gorizia.

_(39295315435).jpeg)

It was inaugurated in 1938 on the Sei Busi hill, a site brutally contested during the armed conflict.

A Visit in Remembrance

The visit to Redipuglia, made by the author of these lines a decade ago, has a logic that is difficult for the visitor to transgress due to the design of the monument.

Upon arrival, we walked along the so-called "via eroica," flanked by bronze plaques, 19 meters in length, with the names of the locations where the bloodiest battles of the war were fought engraved on them.

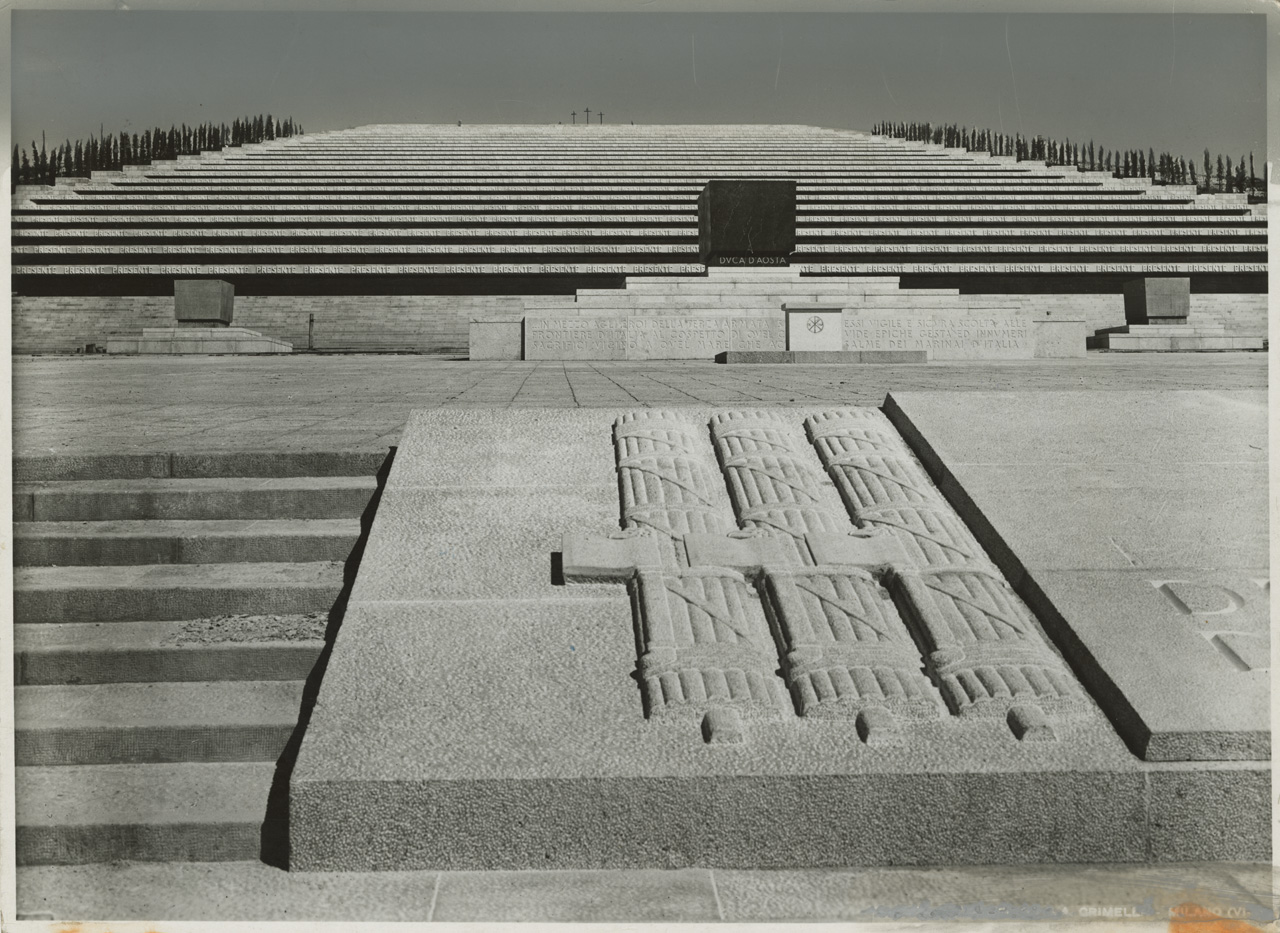

Next, we reached a large esplanade, the base of the monument, where the tomb of Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia-Aosta, commander of the Third Army, is located. He was buried there in 1931 and is guarded on either side by the tombs of his generals.

From there, and occupying the entire slope to the top, a monumental staircase, consisting of 22 steps, over two meters high and 12 meters deep each, lines up the graves of 39,867 identified fallen soldiers.

The visitor can flank this staircase from either end so that they can only access each step transversely. At the top, on the last step, there are two enormous communal graves where 60,330 unidentified fallen soldiers rest.

The entire complex is crowned by three large crosses.

Monumental Architecture and Sculpture

The design of Redipuglia, the work of architect Giovanni Greppi and sculptor Giannino Castiglioni, finds its justification in the defined context of patriotism and the use of remembrance (let us avoid the worn-out and ambiguous political concept of "memory") and the terrible aftermath of World War I by Mussolini's regime.

While the other participating countries in the war maintained a network of national cemeteries in the combat areas (Germany left many of its fallen soldiers to rest in France), the fascist policy was to monumentalize them and insert them into a single body that would erase the last vestiges of individual identity, already compromised by the number and vast proportion of unidentifiable bodies, as Dogliani asserts.

The theatricality of the whole and its immense dimensions inevitably evoke a feeling of disproportionality in the visitor, fueled by the formal structure that is itself conceptually rigid, designed, and executed to pay patriotic homage to death.

On each large step, where the identified fallen soldiers rest, their names and surnames are lined up, almost infinitely, sculpted in white marble, governed by an incessant “present."

The Terrible Experience of War

We would not want to end this commentary, perhaps encouraged by the depersonalization that the list of Redipuglia produces, as some contemporary Italian historians have noted, without mentioning a few words born of the combatants, fallen soldiers, and buried in this monument, in order to approach, however slightly, the terrible personal experience of war.

First, with a testimony that describes the intellectual destruction to which the soldier was subjected by living in trenches, deeply dug into the earth, generally only one meter wide: "Our brains become lazy in the single and limited exercise of everyday life, always the same, underground," wrote Giacomo Morpurgo in a letter in January 1916.

Another testimony, also highlighted by Melograni in his Political History of the Great War, reads as follows:

"We are just a few steps away from the enemy and the war seems distant. (...) Whoever imagines shouts and rifles has made of war a fantastic and conventional idea, different from reality. A decisive action is much more than that, it is a hellish hammer, extermination, a horrendous hurricane of iron and fire, from which one emerges like a cataclysm; but decisive action is rare, it only occurs in the great advances, and it is the ultimate result of a long and complex preparation, which sometimes lasts for months and about which we have only vague and rare indications: (...) an immense, colossal work, which is carried out with a majestic and terrible slowness from week to week, and which we do not precisely alert because of its vastness, although we live inside it."

Perhaps it is daring (even disrespectful) to remember Redipuglia from the sensations that a foreigner may harbor so many years later on his visit to the monument. Its magnificent presence, the infinite list of names, which add their indelible letters as the essence of a majestic white marble whole in its form and terrible in its meaning, provoke deep emotions.

It has not been our intention to be so, and if we have unintentionally done so, we apologize to those who fell in Redipuglia.